Kimberly Sanders walks along the path that circles Lake Estes. She points across the water to a familiar landmark she uses when giving directions.

“That’s the Stanley Hotel. That’s my icon. I say, ‘well if you’re looking at the Stanley Hotel,’ that’s where I tell people you go this way or that way.’

Sanders moved to Estes Park about nine months ago for a change of scenery and because it’s a stable place to maintain her recovery from heroin addiction.

“It's beautiful. It gets me away from the hustle and bustle of everything,” she said. “Estes Park is like a little bubble; a little protective bubble and I like it.

She is enrolled in a medication-assisted treatment program at Salud Family Health Center. It has strict guidelines, including regular urine tests and meetings with her primary care physician and therapist.

“I was at the doctor’s office a lot. So, it interfered with work a lot, but it was either that or relapse or something else,” she said.

Many businesses were forced to reduce in-person services because of the coronavirus pandemic. This included hospitals and health care centers. So, when the health center began limiting in-person visits due to the virus, Sanders panicked.

“I didn’t know what we were going to do,” she said. “I had no clue.”

The rise of telehealth

On April 1, Gov. Jared Polis signed an expanding the use of telemedicine, which provides health care services using audio or video communication. The order allowed rural health centers, Indian health centers and federally qualified health centers, like Salud, to bill Medicaid at the same reimbursement rates as in-person services.

“When COVID hit, really this is not an exaggeration, over the course of a weekend we shut down our clinics and said, ‘we’re going to go to primarily telehealth,’ said Tillman Farley, a family physician and the chief medical officer of Salud Family Health Centers.

Salud serves mainly low-income patients who are uninsured or on Medicaid at its 13 locations around the state. Before COVID-19, the health care organization treated 1,300 patients a day system-wide before dropping to a low of 400 daily visits.

But as telehealth ramped up, so did patient care. About 70% of all appointments are now done over the phone or a video platform, said Farley.

“It’s impossible to overstate the importance of this,” he said. “If they had not passed that legislation, we would have gone out of business.”

Prior to the pandemic, Colorado’s Medicaid program did reimburse for telehealth services, but this was only an option for certain health care providers.

"We actually had a fairly robust telehealth policy which allowed most clinicians to provide telehealth to all members,” said Lisa Latts, chief medical officer for the Colorado Department of Health Care Policy and Financing. “It was a fairly robust policy, but it was very rarely used.”

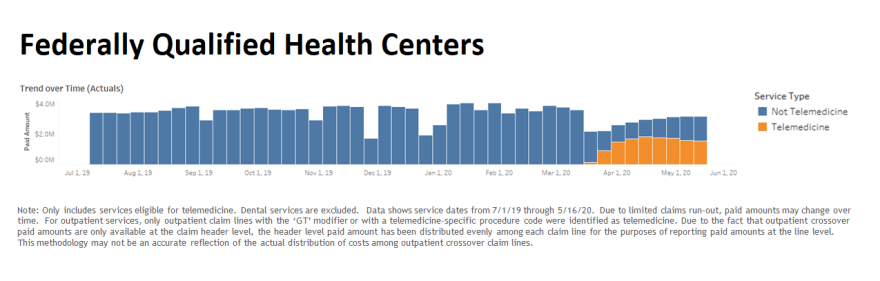

Between April and June, federally qualified health centers billed Medicaid $12,649,670, which was the highest amount billed by a provider type according to state data.

The Colorado Community Health Network, CCHN, is a membership association for 20 federally qualified community health centers.

“Over time, I think telehealth is going to transform the health care system and help with efficiencies,” said Polly Anderson, vice president of strategy and financing for the Colorado Community Health Network. “Telehealth just requires that phone or data connection and two people face-to-face. You don't need as much equipment; you don't need as much overhead.”

But there are still barriers to access. Like older patients who are not as comfortable using technology, or poor broadband, limited cell phone plans or lack of access to a phone.

“We had previously, prior to the pandemic, actually been working on a bill to add this so that we could begin to open up this access point for our patients in Medicaid,” Anderson said.

While the executive order was in effect, a was being debated in the state legislature. Colorado was one of about 40 states to introduce telemedicine according to the Center for Connected Health Policy, which is the federally designated national telehealth policy research center.

“Telehealth before COVID-19 was kind of that unknown actor who's getting a couple roles, nobody knew them,” said Mei Kwong, executive director of the Center for Connected Health Policy. “But then suddenly they were cast in the next Marvel franchise movies and suddenly everybody was talking about them.”

But telehealth will not completely replace in-person services, said Kwong, and it does not work for certain health care services.

“It should be that tool where if the provider thinks it's appropriate to use and if the patient wants it,” she said. “Because (the) patient can always say no I want to come and see you in person.”

Expanding access to care

CCHN worked on the telehealth bill along with the Colorado Coalition for the Homeless, which already had a grant funded telemedicine practice in place, including a newly launched street medicine program.

“I’ve always believed this was the way to go, especially with people experiencing homelessness,” said Ed Farrell, medical director of integrated health services for the Colorado Coalition for the Homeless.

When the new telehealth rules went into effect, the coalition was able to expand these programs and purchase 500 cell phones for people experiencing homelessness. Between 70% and 75% of their clients use Medicaid.

“Where they are, is with lives of tremendous, not fathomable to us really without walking in their shoes, chaos, trauma, and stress,” he said. “So, a telephonic visit meets them where they are. It's the epitome of it.”

The Reimbursement for Telehealth Services bill passed and was signed into law last month, while the executive order ended.

“I was homeless about four years and if they had telehealth back then I probably would have been clean a lot quicker,” said Sanders.

During that time, Sanders worked in Loveland while her doctors were in Fort Collins. She always had a cell phone, but transportation was a major issue.

“If you missed three appointments, you were cancelled, you were no longer one of their patients,” she said. “I got cancelled a couple of times because I couldn't make it.”

That’s in the past now. Sanders is the assistant manager in training at an auto parts store in Estes Park. With telehealth, it’s easy to keep her appointments.

“I just step to the back at work for about 15-20 minutes and then I’m back right at work.”

Sanders is looking forward to the future. She plans to eventually transfer her job to a store in Texas to be closer to her two kids and five grandbabies.

“I don’t want to have to go back to having to go in person,” she said. “It’s amazing how well (telehealth) fits into my life.”